What is it?

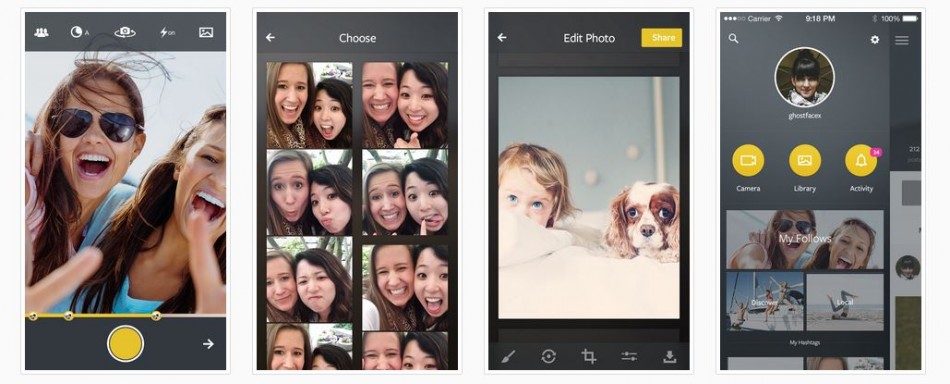

VHOTO is a new app currently only available on the iPhone. It allows users to pick the best images to keep from video captured using the phone. In order to be able to do this – the app scans video detecting “blur, contrast, faces, smiles” in order to present users with a range of significantly different still images. These images can then be shared on popular photo-sharing networks, or through VHOTO’s own platform. In addition to this, VHOTO claims to be a learning software, which is able to generate better image outputs as it learns more about what kinds of images the user wants from the app.

The app allows you to either capture video natively – or import videos captured previously from the camera roll for processing. Processing options include basic adjustments such as contrast and brightness, image orientation, as well as a number of Instagram-style filters. Finally, the app also includes a proprietary image-sharing network which allows users to follow one-another, as well as co-curate content using hashtags.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lsELdVAlaU4

Why is it important?

Resolution “Vanishing Point”

One of the first digital cameras aimed at consumers was bizarrely the Nintendo Game Boy Camera released in 1998 (it was extremely cheap for a digital camera at the time selling at $49.95). It offered a black and white CCD sensor with a resolution of only 256 x 224 pixels. Since this time, one of the main drivers of innovation in the commercial digital imaging area was to produce cameras with increased resolutions (and ergo more faithful and detailed images). Over the course of this development – the unique benefits of digital images were becoming increasingly clear (e.g. easy and “free” copying, and transmission of images over digital networks) – however, there was a clear disparity between the quality of early digital images and those created and printed using photo-chemical means. (Whilst the “resolution” of photochemical images cannot be compared directly to digital, as they are two completely different technologies – depending on the configuration of the film, 35mm film is estimated to be analogous to 4-16MP detail.)

Not only was the Game Boy Camera the first affordable digital camera for consumers – it was also allowed users to take front-facing images, prefiguring today’s obsession with the selfie.

However – perceived image-quality not only relies upon the detail captured within an image – but also, the output display of devices used to view images upon. The original Game Boy’s screen only had a resolution of 160 × 144 pixels – which meant that despite the tiny sensitivity of the Game Boy Camera, it was still greater than the genuine resolution of the display images were mostly viewed on. Theoretically – even if the resolution of the Game Boy Camera had been tripled, or even multiplied tenfold – the perceived image quality seen on screen would remain largely the same to audiences.

This brings us to VHOTO. Today, we rarely print out images we capture using our smartphones – instead sharing them with friends and the public over digital networks. As a consequence of this, we tend to view images on a set of displays which offer roughly the same display resolution (typically HD displays). The monitor which I am currently writing this blog on has a screen resolution of 1280 x 1024 which amounts to a grid of 1310720 unique pixels (1.3MP). My smartphone (a Moto G) has even lower resolution offering 720 x 1280 – just above a 0.9MP display.

As a consequence – the kinds of display that we use to typically view and share images remain largely stable across devices – and are vastly “outsized” by the quality of images we can capture using our smartphones, with rear-facing camera image detail offering a multiple increase on typical display resolutions (Samsung Galaxy S5 16MP, iPhone 5S 8MP). Of course – these cameras now also boast the ability to capture video – at a resolution that would similarly dwarf that of the display the images would likely be seen on at this time.

We can consider this as the current resolution “vanishing point” of capture devices – where the detail (or distortions and digital artefacts) seen within an image upon typical displays become imperceivable. This is also supported by image-sharing networks which regulate or compress image resolution to a proprietary size, such as Instagram, where uploads are compressed into images 2048 x 2048 (4.1MP) in size (notably Instagram images do not allow you to “zoom” in to examine images in greater detail).

Crucially, this means that considering the level of quality of images we can capture using smartphones and the comparative resolution of the displays which we view them on – that images captured directly from video (i.e. using an app like VHOTO) appear perceptibly satisfactory for typical image-sharing purposes. There are of course a number of other factors that influence the clarity of images captured using smartphones – however, for the purposes of this blog, I allege that these coincide with higher sensitivity in smartphone CMOS sensors.

How might it affect the social camera?

The Perpetual Decisive Moment

“Photography is not like painting. There is a creative fraction of a second when you are taking a picture. Your eye must see a composition or an expression that life itself offers you, and you must know with intuition when to click the camera.

That is the moment the photographer is creative. Oop! The Moment! Once you miss it, it is gone forever.”

– Henri Cartier-Bresson (from Washington Post, 2004)

One of the most persistent ideas that has been established within the practice of formal photography is “the decisive moment” by lauded photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson. This concept was based upon the notion of using the camera to selectively record phenomena occurring in the outside world – but at a moment selected by the image-creator to be unique or more significant expression of the subject in a moment in time. This concept can be seen throughout Cartier-Bresson’s work and as a consequence of his (and the Magnum photography collective’s) influence – as a important aspect in formal photographic practice today. Here, skill is attributed to the photographer for their uncanny ability to be in the right place at the right time – as well as capturing a one-of-a-kind image through intuition. (Cartier-Bresson would often wait for hours on end for a decisive moment to happen within a frame).

As such – a large aspect of the notion of what a photographer relies upon the concept that they actively (and selectively) capture images of the world, with a unique vision, skill and intuition. This is something which is completely at odds with the notion of generating images from a stream of video – wherein “the decisive moment” is not captured by the intent of the photographer – but rather reviewed as part of a video, and selected as significant or aesthetic outside of the moment (of in the case of VHOTO presented back to the user as a consequence of an algorithm). There may – as a result be a perceived lack of authenticity, or “intent” read within the image, as it was captured passively.

As such – the ongoing development (and cultural acceptance) of this kind of video-photography technology may influence established understandings of what a photographic image is, and also the active role of the photographer – and the importance of the risk of missing the moment, through lack of photographic vision or skill. (A “photographer” could now wear a video camera all day, and review footage and extract images at a later time).

It also changes the “site” of the decisive moment, to one that is external from what is seen within the image (selection occuring in the editing process), and one that can be repeated many times, by reviewing footage over and over again.

Despite this – some of these ideas have begun to be postulated within the photographic community, with an interesting position being posed by Paul Graham (a leading contemporary photographic artist), who suggested that he may in the future create photographic images from video streams – and furthermore argue their validity.

“The “decisive moment” is bullshit. There are ten pictures before and ten pictures after every one of them: [Henri Cartier-Bresson] actually took thirty pictures of people leaping over that puddle.”

“The question that I do get because of the nature of that work is, ‘Are you going onto film?’ But I’m still absolutely in love with still-photography; the potentials and opportunities are expanding all the time. I see exciting new work every year, and the new opportunities that are coming now are fantastic.”

“In less than ten years we’re going to be able to pull a RAW file out of video, thirty frames per second. And the only reason that anyone can complain – that it’s cheating or whatever – is macho posturing. It’s not cheating, as long as you find the right pictures in that video.”

As a consequence of this phenomena – now being validated by technology in form of the VHOTO app – we may find that the way that we share images socially is affected by a diminishing role on the part of the image-creator (at least in relation to Cartier-Bresson’s concept of recording decisive moments in time).

This to me only suggests the growth of photography in a new and exciting direction, as not the express (and arguably subjective act) of selectively recording of important moments in life, instead toward the autonomous generation of holistic image-worlds featuring moments that would previously be lost in ephemera.

Leave a comment